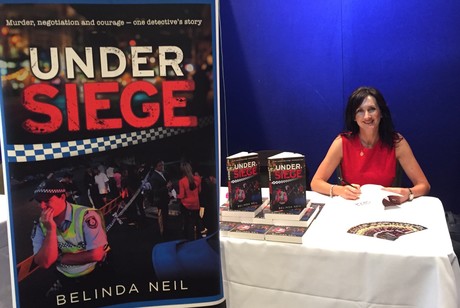

Over 1 million Australians suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 3 million families are affected by it, yet PTSD rates among first responders are much higher than the national average. How can we turn the tide? Former Police Inspector and PTSD advocate Belinda Neil shares her story and her thoughts on how to support first responders.

What was your role prior to retirement due to PTSD?

I had an amazing career in the NSW Police Force. I worked in undercover policing, homicide investigation and hostage negotiation trained to Counter Terrorist Level. Prior to retiring I was working at St George Local Area Command in NSW as a Duty Officer/Inspector in charge of the daily operations of the local area command with 170 staff. I saw many horrific crimes scenes and was involved in over 150 High Risk Negotiation situations including one where a man ran at me with a carving knife and got to within 30 cm before he was arrested by tactical police. I was eventually diagnosed with PTSD and medically retired after 18 years.

Can you share some instances in your career that contributed to your PTSD?

The murder of Kim Meredith, a beautiful 19-year-old girl who was brutally murdered in Albury. Her throat was cut, like an animal in an abattoir, and her clothes apart from her socks removed. She was left sitting under a light in a carpark.

After an intense investigation, Graham Mailes was charged with her murder. Over seven years there were a number of trials and I got to know her parents Bob and June, and her brother Graeme, very well. Beautiful people.

As the court cases continued and my children were born, I found I was unable to keep up protective emotional barriers from the horrific nature of the crime. I started having horrendous nightmares of this and other crime scenes; I was hyper vigilant, I couldn't relax taking my children to the park, I just needed to be home in my sanctuary. I was irritable; I had difficulty concentrating and was very forgetful, even forgetting basic things like showering, putting on deodorant and eating... I was diagnosed with PTSD and major depression. My marriage broke down and I considered taking my own life.

It was only when I finally accepted I had PTSD that I was able to start to manage it and get the right help. I am still recovering, however, my thoughts are still with the incredible grief suffered by the family of Kim Meredith.

The hostage situation was one where an ex-boyfriend held his former girlfriend hostage in the bedroom of her house. He had two knives held against her neck to which he made superficial cuts. It was far too dangerous for tactical police to resolve the situation as he could easily kill her before they could enter the room.

The negotiation took over eight hours before he eventually released his hostage and surrendered to police. I will never forget the look of terror on the hostage’s face, her white shirt stained red with her blood, and feeling helpless at not being able to do more for her but standing, watching and talking from the doorway. I had many flashbacks to this situation later.

In your opinion, why are first responders, like police officers, likely to experience PTSD?

PTSD is a set of reactions that can occur after exposure to traumatic events. First responders like police, ambulance officers, paramedics and firefighters attend traumatic events including horrific crimes scenes, serious road accidents, life-threatening fires and more, every day; as do emergency nurses and trauma surgeons. First responders do this so we as a community can sleep soundly at night.

A leading expert in PTSD, Professor Alexander McFarlane of the University of Adelaide, said. “Even the healthiest individuals will become unwell when exposed to enough trauma.” Scientia Professor of Psychology Richard Bryant, from the University of New South Wales, advises that 10% of first responders are likely to get PTSD compared to the national rate of 4%.

Based on your experience, how is PTSD handled by the police force?

The latest figures for NSW Police are 300 police officers are retiring every year and 95% of those have PTSD. I think this is a shocking figure and I am disappointed that 13 years after I was medically retired with PTSD, their mental health and wellbeing programs are still not effective.

I am aware of some great early intervention initiatives that have been put into place by other police agencies and first responder groups which are evidence-based, so I believe the tide is turning and first responder agencies are really starting to address the issue of PTSD for their officers.

Does early intervention help first responder sufferers manage their PTSD?

Early intervention is the KEY to preventing and minimising PTSD. One of the first things a PTSD-affected person loses is their ability to monitor their own emotional state and track their internalised world. This may explain why I never believed I had a problem. If I had known, I could have sought assistance many years earlier and perhaps my symptoms would not have been so severe. The earlier that support is given to a first responder, the better the chance they have of minimising its effects.

What types of intervention works best for first responders?

Early intervention, which can involve:

- trauma tracking — supervisors tracking their individual team members’ trauma load;

- supervisors identifying potentially psychologically affected officers;

- discreet one-on-one conversations between the injured officer and an appropriate supervisor with follow-up and support;

- removal or respite from frontline duties or from further exposure for a specific period;

- referral to mental-health professionals, either in-house or outsourced psychologists, who MUST have expertise in recognising and treating PTSD;

- education on how to communicate with potentially affected officers and how to manage officers who have a psychological injury.

The credibility of both supervisors and mental health professionals is paramount, otherwise the psychologically affected officer will never declare his or her concerns.

Why is more discussion needed on PTSD?

There are currently around 3500 groups in Australia working on different aspects of PTSD yet there is no national forum to bring people together and share their experience and knowledge. A conversation is the best way to build new relationships with like-minded people and create vital networks. And lastly, to get action from our political leaders, we need to come together with one voice. Then we can get things done!

Supporting the wellbeing of Australia's firefighters

Academics Dr DAVID LAWRENCE and WAVNE RIKKERS detail their continuing research in the area of...

Software-based COVID-19 controls help protect onsite workers

The solution decreases COVID-19-related risks by ensuring that contractors and visitors are...

Spatial distancing rules: are they insufficient for health workers?

Researchers have revealed that the recommended 1- to 2-metre spatial distancing rule may not be...